The first weekend of June, my three boys ran the San Diego Half Marathon with me. How did I get three teenagers to run 13.1 miles? Consider two things. First, the race was part of the Rock ‘n’ Roll Running Series promising a band every mile. Second, they agreed back in December; I’ve learned kids will agree to pretty much anything if the commitment seems forever in the future.

While there weren’t as many bands as expected – and some appeared and sounded unofficial (although the very unofficial karaoke singer ripping up Gimme Shelter at Mile 10 proved motivating) – the kids did great. 18-year-old Leo ran way ahead, leaving me with 15-year-old Hal and 13-year-old Zev. Neither had trained; Hal dismissed it as unnecessary, claiming he could will himself to run a half marathon. Both ended up running at a respectable 8:45 pace without any complaints or even labored breathing. This allowed me to enjoy the run. We passed full bars serving tequila shots, bloody marys, and steins of beer. There were tables of donuts and muffins; we could have had a full brunch en route. And we passed thousands of spectators holding signs, the most memorable of which were:

WORST PARADE EVER

and

THIS PARADE SUCKS

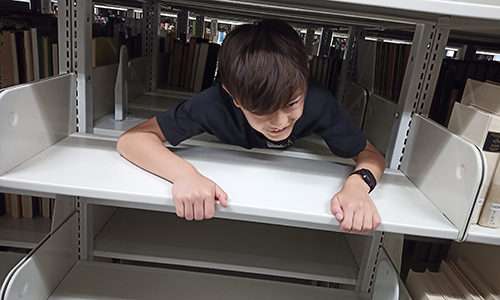

But this wasn't the highlight of our San Diego trip. As you might guess, I like to visit college campuses. We checked out two that weekend: Point Loma Nazarene and UCSD where a rising sophomore family friend toured us through his Muir College dorm and Geisel Library, which provided a terrific vantage point for Fallen Star, the cute cottage tilting off the edge of the engineering building. In Geisel’s basement, Zev made a beeline for the high-density rolling stack shelving. It was game on. Zev ran into an aisle and challenged his brothers to make it disappear. They’d furiously spin the wheels, forcing Zev to jump up to an empty shelf and burrow in before facing a Star Wars trash-compactor-like fate. After a few escape acts, Zev couldn’t be found; it turned out he’d tunneled his way through five or six shelves to the daylight of an open aisle. Here’s what that looked like on the other side:

***

The worst parade ever + Library Dig Dug wasn’t my first time in San Diego this year; I’d been there in April for the ASU-GSV conference. In contrast to artificially dumb shelving antics, ASU-GSV 2024 was all about artificial intelligence. Presentations and panels focused on strategies for deploying AI in the classroom and other student-facing applications. I’d expected as much; these are the first things that come to mind. It’s the glamour work, or what passes for glamour in education. Similarly, pundits, technologists, and futurists have been hard at work predicting how AI will transform the classroom via developing lesson plans, identifying additional learning resources, rewording resources to make them more accessible or age-appropriate, building formative assessments, grading, learning analytics, and the Holy Grail: personalized instruction and tutoring.

Touting AI’s infinite adaptability and patience with students, most of the attention is on this last point. The star so far is Khan Academy’s Khanmigo. Sal Khan has hyped the opportunity to the New York Times: “We’re at the cusp of using AI for probably the biggest positive transformation that education has ever seen. And the way we’re going to do that is by giving every student on the planet an artificially intelligent but amazing personal tutor.” Political leaders are equally stoked: a White House executive order directs federal agencies to “shape AI’s potential to transform education by creating resources to support educators deploying AI-enabled educational tools, such as personalized tutoring in schools.” And Khanmigo – now powered by Chat GPT-4o’s impressive multimodal capabilities – is far from the only AI tutor; Microsoft and Google have already launched bots for schools and districts are racing to utilize these platforms or build their own in a last-ditch attempt to address Covid learning loss.

But there’s no indication AI can do any of this yet. In the On Edtech blog, Glenda Morgan is “unconvinced that the kinds of tutoring currently offered via AI matches the concept of watching a student’s thought processes and identifying the core issues they aren’t understanding. Instead, AI tutoring today seems to consist of breaking down problems into component parts and explaining the components. This is no doubt helpful, but it is not tutoring in the true sense of the word.” According to Satya Nitta, who led a $100M initiative at IBM to make AI work for tutoring, tutoring “is a terrible use of AI.” Nitta believes “we’ll have flying cars before we will have [effective] AI tutors.”

The common thread seems to be that technologists – even experts in machine learning – don’t understand how human learning actually works. “It is a deeply human process… like being a therapist or like being a nurse,” argues Nitta. Reach Capital Co-Founder Jennifer Carolan makes the point that “our brains are uniquely primed to learn from and with other humans.” So although it’s certainly possible to learn from AI (or a book or video for that matter), there’s no evidence AI can teach at scale – at least not students who need the most help. It may be that – as with online math programs – only highly motivated and prepared students are able to take full advantage. In terms of teaching and learning, AI could be an inequality accelerant.

For faculty, AI is already increasing research productivity. But don’t expect a sea change in teaching. Witness limited progress on transitioning from lectures to active learning: while 82% of faculty are aware of the benefits of evidence-based teaching strategies, only 47% report having adopted any. Because it’s as much work as developing a brand-new course. Which raises the question, what will be the primary impact of AI on schools? Reach Capital’s Carolan hopes that AI “will end busywork.” I think she’s right. And there’s much more busywork to end outside the classroom.

***

Teldar Paper has 33 different vice presidents each earning over 200 thousand dollars a year. Now, I have spent the last two months analyzing what all these guys do, and I still can't figure it out. One thing I do know is that our paper company lost 110 million dollars last year, and I'll bet that half of that was spent in all the paperwork going back and forth between all these vice presidents.

- Gordon Gekko, Wall Street

With enrollment and budget challenges about to shift from manageable to four- and five-alarm fires from this year’s FAFSA fiasco and next year’s enrollment cliff, many college leaders will be taking a fresh look at where all the money is being spent. Hint: it’s not teaching and learning. As a percentage of the higher education workforce, faculty is just over 1/3. In terms of total spend, instruction represents a bit less than 1/3. So while the knee-jerk reaction might be to eliminate programs and departments – many small colleges are already heading down this road – a more promising approach is cost reduction via reinventing business processes. This is where AI comes in.

While colleges and universities may be more efficient than Gordon Gekko’s takeover target, it’s probably a close run thing. In the past generation, higher education institutions have increased enrollment by 78%, faculty by 92%, administrators by 164%, and other staff by a whopping 452%, including tens of thousands of deanlets. According to the Progressive Policy Institute, many schools have three non-teaching staff for every teacher.

With dozens of departments and hundreds of business processes at every institution, AI has the potential to automate routine tasks and produce efficiencies in at least 24 areas:

|

|

Figuring out how to leverage AI in each will require discrete initiatives which won’t be undertaken all at once. They can’t be; each is tantamount to changing your shoes while running a half marathon. The upside is that institutions can use AI to help i.e., AI-driven process mining. The results will probably involve upgrading software platforms used to manage these functions – or introducing new AI-powered software – then reengineering current businesses processes to maximize automation. Colleges will find it’s possible to improve service levels (including anticipating problems and resolving them before they become big problems) with a non-teaching-staff-to-teacher ratio that’s closer to 1:1 than the current 3:1. And that means a much longer runway for addressing the core value proposition and growing enrollment once again.

No one has ever gone broke betting against the pace of change at colleges – unless and until they have no choice. Enrollment challenges and budget cuts will be higher education’s forcing function, as well as for K-12 school districts while red states encourage families to opt out of public schools. I plan to let Zev know that AI will also make libraries more efficient. And efficiency means no empty shelves in high-density rolling stacks, and no way for trapped children to save themselves.

While Zev avoided getting shrunk in the high-density rolling stacks, colleges shouldn’t try to avoid it. They should embrace AI in order to shrink. If they do, they won’t have to blame student protesters for downsizing. They’ll be able to blame the other big story of 2024: AI.

***

For decades economists have castigated healthcare and education – the two largest sectors of the economy – as brakes on productivity growth: no matter how good technology gets, an individual doctor or teacher can only deliver services to a limited number of people. And higher education’s budget challenges are partly a product of Baumol’s cost disease, which states that in order to compete for talent, low-productivity-growth sectors like education must increase wages on par with high-productivity-growth sectors, thereby making education prohibitively expensive.

The hope has been that new technology for delivering education – online education, MOOCs, AI tutoring – will remove the productivity bottleneck and rationalize costs. But in paying so much attention to teaching and learning, we’re like the drunk stumbling out of a bar, trying to find his car keys, looking under the streetlight because that’s the only place he can see. At schools, the lights are on classrooms. But the money is spent on everything else.

As AI takes root in colleges and universities over the next few years, it's impossible to say which deanlets will disappear, only that colleges won’t need nearly as many of them. And as AI ushers dozens of deanlets out the door, it will prove the San Diego sign-holder wrong. Because that will be the worst parade ever.