Volume IV, #17

Growing up in Toronto in the 1980s, if I thought about university at all, it was about the relative merits of London, Ontario (Western University) versus Kingston, Ontario (Queen’s University). There was no question about going to University of Toronto. That was for losers who wanted to live at home.

If I thought about U.S. universities at all, it was all about the Ivy League. Why take the trouble to go down there unless you were going to an Ivy League school? What else was there in the States? And if there were other universities, surely they’d want to be like the Ivy League.

If Canadians – so close most could pass for Americans – are afflicted with Ivy League myopia, what hope is there for the rest of the world? Little I’m afraid, particularly if you’re on the other side of the world.

***

Bhutan is a Himalayan kingdom of 750,000 people on the other side of the world, sandwiched between India and China.

Really, really far away.

Really, really far away.

It is known as the home of the yeti or abominable snowman, but perhaps best known for the concept of Gross National Happiness – a concept coined in the 1970s by Bhutan’s fourth Dragon King, Jigme Singye Wangchuck. More recently, Bhutan established a Gross National Happiness Commission to review laws and regulations, similar to how environmental impact reviews are conducted in developed countries.

Perhaps Bhutan focused on measuring Gross National Happiness because it didn’t perform well in the traditional measure of Gross National Product. Its economy was wholly agricultural until the last decade when hydroelectric power stations began coming online. Then Bhutan hired McKinsey to identify new areas of economic growth in order to produce 90,000 new jobs. From 2008 – 2012, Bhutan spent 9% of total public expenditures on McKinsey consultants (a remarkable achievement). Amongst the initiatives spawned was Knowledge City: a higher education hub that would transform Bhutan into a knowledge economy.

While McKinsey was charged with the high-level strategic thinking and came up with Knowledge City, Knowledge City implementation was left to other consultants like one Big 4 firm, which won the Knowledge City work by convincing the government that Bhutan’s political stability and pristine environment would attract 15-30 world-ranked universities, enrolling 40,000 foreign students. In its winning presentation, the Big 4 consultancy is said to have referenced its ability to persuade an Ivy League university to open a branch campus in Bhutan.

The Education Minister was quoted as saying the Ivy League school and others would “bring in examples of good practices [and] we’ll stand to gain in terms of our being able to participate in the intellectual exploration these institutions are known for… Our national intellectual profile will be enhanced. We’ll also benefit through job creation that [the project] will make possible. The coming of… a number of world-class colleges and institutions will be a wonderful investment.”

So this was the plan the Bhutanese government chose for Knowledge City, an economic development project for a country with a 47% literacy rate. And did I mention that Bhutan is really, really far away?

***

As in most emerging economies, the government’s tool of choice for creating Knowledge City was land. According to the Prime Minister at the time, “using land [to create Knowledge City] is the most logical thing to do. If we don’t put land, we have to put money.” So in February 2010, the government granted 1,000 acres to its investment arm (DHI). Coincidentally, the selected site was very close to land owned by the Prime Minister, the Speaker, and the wife of the former Works and Human Settlement Minister. Not long thereafter, the Education Minister’s wife bought the immediately adjacent parcel.

The firm DHI contracted with was Infinity Techno Parks, an Indian firm that said it would invest $1B in the project. It turned out Infinity was a small construction company with a track record of 12 buildings in and around Kolkata, including an office building for IT companies called the “Infinity Think Tank” that was a “model of environmental and futuristic aesthetics.”

The government pulled the plug on Education City earlier this year, after the government had spent millions more building a bridge and approach road. Shockingly, no Ivy League school nor any other ranked university had any interest in locating in Bhutan. The only winners were consultants, land speculators and contractors.

***

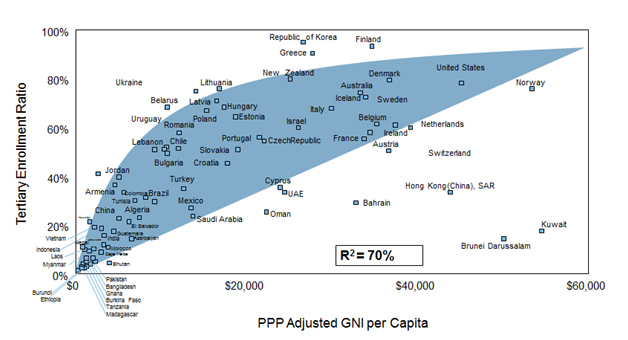

The losers were the people who could least afford it: the people of Bhutan. While economic development is highly correlated to participation in tertiary education, the correlation is tightest and steepest for low income countries like Bhutan seeking to attain middle income status.

Currently, only 10% of graduates from the secondary level go on to tertiary education in Bhutan. Another 10% attend universities in India. So rather than thinking about the Ivy League and attracting tens of thousands of foreign students, Bhutan would have been better served by contracting with a U.S. community college system or large private sector institution, either of which would have done much more to increase higher education participation and further economic development.

But Education Ministers in emerging economies don’t get excited about University of Phoenix. They get excited about the Ivy League. That’s unfortunate, because what makes America’s system of higher education the best in the world is not the Ivy League, but rather the diversity of its institutions, which contribute to its high level of participation.

Consultants like McKinsey and Big 4 firms know better and should say so instead of taking advantage of Ivy League myopia in order to sell a plan to the land of the abominable snowman that turns out to be an abominable snowjob.

Thanks to Ankit Dhir of UV and Karan Khemka of Parthenon who contributed to this Letter.

University Ventures (UV) is the premier investment firm focused exclusively on the global higher education sector. UV pursues a differentiated strategy of ‘innovation from within’. By partnering with top-tier universities and colleges, and then strategically directing private capital to develop programs of exceptional quality that address major economic and social needs, UV is setting new standards for student outcomes and advancing the development of the next generation of colleges and universities on a global scale.

Comments