Volume V, #18

“I went to the Wharton School of Business. I'm, like, a really smart person.” - Donald Trump

“These are stupid people that say, ‘Oh didn't Trump declare bankruptcy? Didn't he go bankrupt?’ I didn't go bankrupt.” - Donald Trump, after filing for bankruptcy on four of his businesses

It is a near certainty that no presidential candidate in history has used the words "smart" and "stupid" as often as Donald Trump. Listening to Trump speak is to witness a battle between smart and stupid.

The most amazing thing about the Trump phenomenon is not that he continues to lead polls despite the things he says, but rather that Americans believe he’s a successful businessman. Trump is an entertainer playing a successful businessman. His “business” is licensing his name to businesses. Trump was once primarily a principal owner and investor until lenders began steering clear. When the numbers went south, Trump had a bad habit of going back to his lenders and saying: I could let the entire project go, or I could pay you back 50 cents on the dollar. Or as Trump says: “We’ll negotiate with the banks. We’ll make a fantastic deal.”

Of course, Trump is best known for his role on NBC’s now cancelled Apprentice and Celebrity Apprentice where candidates competed for a management job in the Trump organization, and where employer Trump “fired” them before they were hired. Trump played the tough boss who somehow managed to find fault with candidates like Andrew “Dice” Clay, Dennis Rodman and Meat Loaf. Heck, Trump “fired” Gary Busey and Geraldo Rivera. If Donald Trump has anything in common with real American employers, it’s his fickleness.

***

One of the “huuuuuge” challenges in the U.S. economy that Trump will have to solve in the apocalyptic event he is given the opportunity to “Make America Great Again” is that U.S. employers think new hires are not adequately prepared for open positions. U.S. employers are developing a global reputation for wanting the perfectly qualified candidate delivered on a silver spoon – or they won’t hire. As Peter Capelli of Wharton astutely notes, “employers are demanding more of job candidates than ever before. They want prospective workers to be able to fill a role right away, without any training or ramp-up time. To get a job, you have to have that job already.” He calls it the “Home Depot view of the hiring process,” where filling a job vacancy is “akin to replacing a part in a washing machine.” The store either has the part, or it doesn’t. And if it doesn’t, the employer waits. The result is that while there are over 8M unemployed workers, we have over 5M unfilled jobs, and perhaps as many articles featuring employers whining about unprepared workers.

In his wonderful monograph “Why Good People Can’t Get Jobs,” Capelli says we have a “Skills Standoff,” with employers dissatisfied with the level of new hire preparation but unwilling to provide training or otherwise engage in skill-building activities with candidates. One major reason? Employers don’t want to risk investing in employees who may leave the company soon after.

And so the supposed skill gap is a byproduct of a trust gap. How can we get employers to trust new hires and engage in training and skill-building? Likewise, how can we get candidates to invest in their own skill-building – perhaps even skill-building specific to an employer – so that employers find the “right part in a washing machine?”

Capelli says solving the skill gap requires a rethinking of the financing of employee training and suggests a range of options that share the cost and risk between employers and employees, and between the public and private sectors. While we think Capelli’s formula is correct, believing that employers or candidates can or will lead a solution is tantamount to believing that the Bush-Clinton battle many expected to see this political season gets pushed out of the media spotlight without a third party interloper or intermediary like Donald Trump. It takes a Trump-like intervention to solve a generation-spanning problem like Bush-Clinton.

***

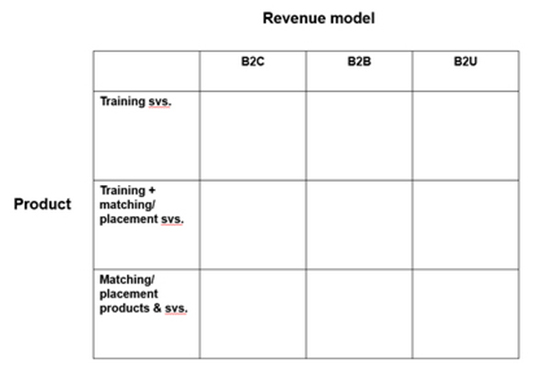

A variety of intermediaries are emerging at the intersection of higher education and the labor market in an area we call “Pre-Hire Training.” Some focus solely on training. Some focus on training + placement or matching services. Others focus solely on matching candidates with employers. In terms of revenue, some seek revenue from job seekers. Others generate revenue from employers. Still others attempt to charge education providers. The result is a matrix that looks something like this:

What these emerging intermediaries have in common is the following:

Intermediaries can set up structures and programs that encourage employers and candidates to trust one another. For example, intermediaries that are confident in their ability to train and place candidates, and thereby attract employers, can guarantee some outcome to candidates to bring them in the door in the first instance. This could be a guaranteed interview, or even a job guarantee if they successfully complete the pre-hire training.

Emerging intermediaries at the intersection of the higher education and labor markets are in the early stages of establishing the necessary structures to close the trust gap, and thereby close the skill gap. Unlike Donald Trump’s credibility with banks, this is a trust gap that can be bridged. And unlike an untrustworthy entertainer playing a businessman playing a presidential candidate, these intermediaries have real potential to materially improve labor market productivity and make America even greater (again).

University Ventures (UV) is the premier investment firm focused exclusively on the global higher education sector. UV pursues a differentiated strategy of 'innovation from within'. By partnering with top-tier universities and colleges, and then strategically directing private capital to develop programs of exceptional quality that address major economic and social needs, UV is setting new standards for student outcomes and advancing the development of the next generation of colleges and universities on a global scale.

Comments