Volume III, #16

Where I went to school, the traditional post-graduation path was to find a job, move to New York City and live in a small space with a large number of people. And so I duly got the job, found the apartment – three renovated bedrooms, on 101st and West End – and recruited Yahlin, then my girlfriend (now wife) and four others to fill the space/rent.

Six people in three bedrooms? There were two tricks to that. The first was convincing two of Yahlin’s friends to room together and split rent. As both had entry-level jobs in publishing, this was a snap. The second was creating a fourth bedroom so Yahlin and I weren’t sleeping in the living room. Fortunately a set of new French doors demarcated a small dining room from the living room. My mission was clear: wall off the French doors to create a bedroom from the dining area. As everyone else had begun working, I not only had a significant privacy incentive, I had the time. Mr. Gorbachev, I would build that wall!

With no car, the project involved borrowing a flatbed dolly from the hardware store at 96th and Columbus and ferrying plywood, two-by-fours, soundproofing insulation and paint to the apartment. Construction and painting took about two days. When I was done, five of us gathered to raise the wall and our glasses to our fourth bedroom.

I have a visceral, Proustian memory of pride associated with that Wall. Woe to anyone who questioned its construction, let alone its existence. Woe befell our sixth roommate, a Franco-German classmate and rookie investment banker whose work schedule and demanding girlfriend kept him away from the apartment for days at a time. Nearly a week after the rise of Wall, he returned home and saw to his horror that the French doors – the highlight of the apartment – were now hidden from view. He pounded the table to demand their release and – failing that – a reduction in his rent.

In retrospect, I regret that over the next few months I conspired with other roommates to make life difficult for our French French door lover. Our relationship degenerated to the point that we didn’t see him for months at a time. I now see that my passion for antagonizing him stemmed not only from the highly valued privacy he threatened, but from my love for the Wall itself.

***

As with most new graduates, our apartment was also an IKEA showcase. After the Wall, following iconic assembly instructions to assemble Billy bookshelves and Ingo tables was a joy and I felt a similar sense of pride surveying our Nordic furniture.

If you’re not familiar with IKEA, please “take a chance.” There’s a lot more to it than the delicious Swedish meatballs and lingonberries they serve in the cafeteria. Jonathan Coulton’s song IKEA is a useful primer:

Long ago in days of yore

It all began with a god named Thor

There were Vikings and boats

And some plans for a furniture store

It's not a bodega, it's not a mall

And they sell things for apartments smaller than mine

As if there were apartments smaller than mine

Ikea: just some oak and some pine and a handful of Norsemen

Ikea: selling furniture for college kids and divorced men

Everyone has a home

But if you don't have a home you can buy one there

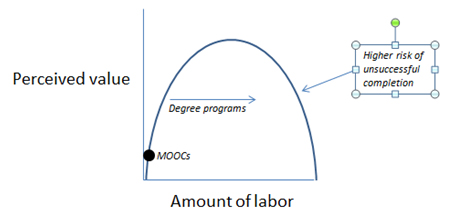

We’ve been thinking about IKEA in the context of valuing higher education. Duke University’s Dan Ariely has documented what he calls the “IKEA effect” and determined that successful completion of a labor-intensive task yields to higher perceived value, or love. In a 2012 article in the Journal of Consumer Psychology, Ariely and his co-authors discuss how instant cake mixes in the 1950s only began to take off once manufacturers changed the recipe to require adding an egg. The IKEA effect certainly explains the strong feelings I had for my Wall and Billy bookshelves (which we still have in our home today, to Yahlin’s chagrin). It also explains the success of organizations like Habitat for Humanity, where new homeowners help build their homes. 98% of Habitat homeowners report moderate to high self-esteem after moving into their Habitat home.

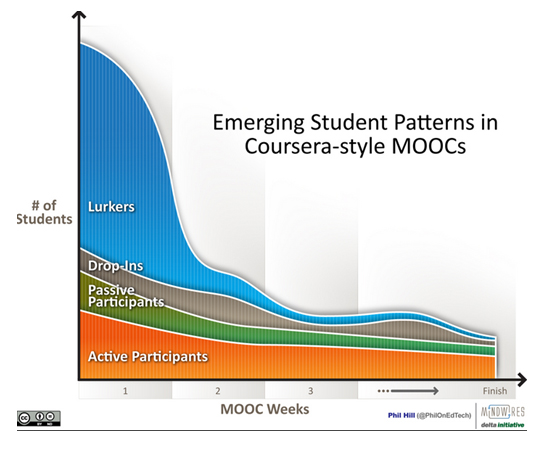

So when we learn that students are completing MOOCs at an unacceptably low rate, one reason may be that our current paradigm – reinforced to date by the inability of MOOC providers to provide a value-bearing credential – is that a MOOC is equivalent to Step 1 in a 40-step IKEA assembly instruction. Step 1 isn’t that much work, and not much perceived value or love is generated from completing Step 1. It’s only by completing all 40 steps and viewing the finished product (i.e., credential) that love is produced. As illustrated below, most MOOC students abandon Step 1 upon unpacking the box, looking at the complex instructions and deciding that it’s too hard.

“At the same time,” Ariely warns, we “should also be careful to create tasks that are not too difficult as to lead to an inability to complete the [product]; again, our results demonstrate that labor leads to love only when that labor is successful.”

Value-bearing credentials like certificate and degree programs are clearly labor-intensive products, but they need to be completed for that labor to turn to love. We visualize the IKEA curve for higher education as follows:

Beyond a certain point, there are negative returns to labor in higher education. As it gets harder and hard to complete a value-bearing credential, the perceived value by students will be lower. The IKEA curve helps explain why many students continue to favor liberal arts over more difficult-to-complete STEM programs (where drop-out rates approach 50%) despite clear signals to the contrary from the labor market. And it may explain why the perceived value of transfer colleges and DIY paths remains low despite much lower price points (i.e., the additional labor required to navigate to successful completion of a value-bearing credential lowers the perceived value).

***

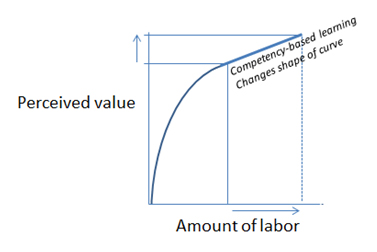

From this Nordic perspective, the good news for higher education is that competency-based learning continues to gain momentum. In the current seat-time model, what failure really means is that students did not achieve the prescribed outcomes in the time allotted. They timed out. In contrast, in a competency-based model, failure is not an option. Students are provided all the time they need to gain and then demonstrate required competencies. Transfer credits become anachronistic; if you’ve demonstrated the competencies, you move forward. The result could be a radical change in the shape of the IKEA curve.

If so, competency-based learning could result in more work and learning than the current seat time model and the resulting perceived value should be higher as a result.

So if you’re thinking of going back to school, consider competency-based programs like those offered by Western Governors, Patten, and Southern New Hampshire. And if all you can think about is getting that damned Bjursta table assembled, think about it in a competency-based way. You have all the time in the world to complete it. Relax. Put on some Abba music. Take it one step at a time.

You’ll love the result.

Peter Enestrom, who thinks about IKEA even when he’s not assembling furniture, provided the concept for and co-wrote this letter.

University Ventures (UV) is the premier investment firm focused exclusively on the global higher education sector. UV pursues a differentiated strategy of ‘innovation from within’. By partnering with top-tier universities and colleges, and then strategically directing private capital to develop programs of exceptional quality that address major economic and social needs, UV expects to set new standards for student outcomes and advance the development of the next generation of colleges and universities on a global scale.

Comments