UV Letter - Volume III, #5

It was Napoleon who famously said “in politics, stupidity is not a handicap.” This adage encapsulates much of what happens in Washington, DC, where a panoply of apolitical issues are bogged down in political gridlock. It’s a natural result and desired goal of the “controversy-industrial complex” – a phenomenon that profits from controversy. Media, think tank, lobbyist and government professionals – intelligent and educated individuals all – spend their lives devising how to turn conventional wisdom on its head and transform benign topics into heated political debates. Stupidity is definitely not a handicap for these folks.

There is no reason online education should become embroiled in political controversy. But that doesn’t mean the controversy-industrial complex won’t try, especially when online education has been getting so much positive attention recently. In a February 18 editorial titled “The Trouble With Online College,” The New York Times dismissed online education as a plaything for the privileged, saying online courses “are inappropriate for struggling students… who need close contact with instructors to succeed.” Then, at the end of that week, Salon published “Conservatives Declare War on College” by long-time staff writer Andrew Leonard. In the piece, Leonard concludes that “there is a crucial difference in how the Internet’s remaking of higher education is qualitatively different than what we’ve seen with recorded music and newspapers.” That difference, of course, is that “There’s a political context to the transformation.” Leonard’s logic goes something like this: higher education should be publicly funded; conservatives want to defund higher education; the Republican governors of Texas, Florida and Wisconsin, the “three horsemen of the MOOC apocalypse” are not only seeking to lower the cost of higher education, they are “leading the push to incorporate MOOCs into university curricula.” Ergo MOOCs are a conservative Trojan Horse. And online education is guilty by association, particularly because, according to Leonard, humanities can’t be taught online, so an online future means less humanity, more conservatism.

To deny stupidity another victory, let’s first address these arguments:

***

The New York Times editorial may have been driven by the perceived success (at least within the controversy-industrial complex) of its investigation of the virtual schools company K12. The article “Profits and Questions at Online Charter Schools” published last fall caused the company’s stock price to fall 25% and riled up long-time critics of the company.

If the Times’ attack on online higher education fell flat, it was due to one key distinction. In K-12 education, there are over 3.2 million public school teachers. While grade levels, subjects and specialties differ, as large constituencies go this one is highly homogeneous. Public school teachers are charged with the instruction of public school students, and they are notoriously protective of public school funding, and equally militant against challenges to that funding, and their jobs and authority. Most K-12 innovations or reforms fairly fall into one or the other category, and the result is real political controversy – not manufactured.

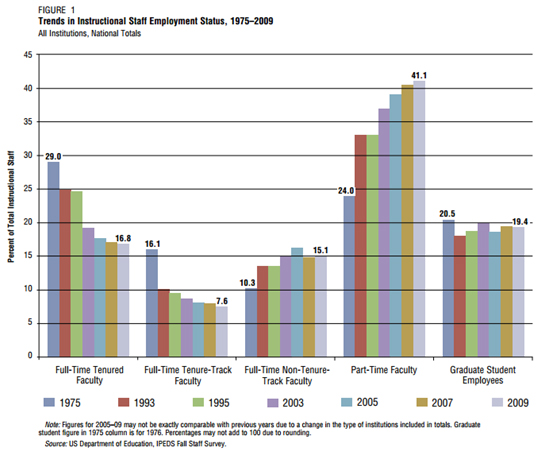

In higher education, there is no such monolithic constituency. In fact, the median figure in higher education is not the full-time tenured faculty member, but rather the part-time non-tenure track adjunct. So while we know who’s teaching public school students, but most observers are surprised when they learn over 75% of instruction at our colleges and universities is delivered by either graduate students, part-time faculty, or full-time non-tenure track faculty.

There are many reasons for this dramatic shift. But its relevance to the issue at hand is undeniable: attempts to politicize online higher education are destined to fall flat. Part-time and adjunct faculty members are primarily interested in more work and steady work. They are likely to be in favor of online programs that have the potential to add enrollment.

Overall, there has been little faculty opposition to the launch of online degree programs at traditional universities. And what opposition there has been has not received much attention. Even in the University of California System, union concerns and threats about online programs have been met with clear statements from the system that the union has no power whatsoever to block new programs. According to the System, all the union could do is “provide written notice saying, ‘We don’t like this.’” Elsewhere, opposition has been typically framed in the form of concern around quality, viability of the business model and – most of all – how much faculty members are being paid.

To the limited extent opposition is continuing, in a New York Times-ish effort to draw a straight line from K-12 politics, it is oriented not against online education, but against the “for-profit” service providers that assist universities in developing and delivering the programs. Here’s a recent e-mail from the AAUP chapter at Rutgers to faculty members:

“Rutgers University has signed a contract with Pearson, one of the largest corporations in the field of publishing, assessment services and on-line education. We have obtained a copy of the contract specifying how Rutgers would develop the on-line degree programs that Pearson would manage. We make the Pearson Contract available to you and invite your comments… While this new relationship with Pearson may well change the nature of education at Rutgers, the agreement was signed without any real consultation with faculty.”

But this won’t fly either. When California’s Democratic Governor Jerry Brown stands next to Sebastian Thrun of the “for-profit” company Udacity to announce a transformative partnership with San Jose State University, it becomes impossible to politicize public-private partnerships. Likewise, I’m not sure what happens to the “three horsemen of the MOOC apocalypse” when they encounter Jerry Brown at the National Governors Association. Is he the fourth horseman? Or is he the anti-horseman who makes the three horsemen disappear in a poof of illogic? (Of course, the great irony of the fact that the Salon article focused on MOOCs is that faculty who are truly against online education should support MOOCs, as they’re a sideshow likely to distract and delay institutions from developing real online programs.)

To demonstrate the same point with online degree programs: While Western Governors University has now developed branches in Indiana, Texas, Tennessee and Missouri, WGU Washington now enrolls over 3,000 students online. While it might seem counterintuitive to those seeking to politicize online education, demand for affordable higher education isn’t limited to conservatives.

And so despite the best efforts of our political friends, online higher education will be just fine. Because in higher education, stupidity is a handicap.

University Ventures (UV) is the premier investment firm focused exclusively on the global higher education sector. UV pursues a differentiated strategy of ‘innovation from within’. By partnering with top-tier universities and colleges, and then strategically directing private capital to develop programs of exceptional quality that address major economic and social needs, UV expects to set new standards for student outcomes and advance the development of the next generation of colleges and universities on a global scale.

Comments