UV Letter - Volume II, #19

Summary: Beer industry market segmentation is employed as an analogy for the online learning market. These segments provide different answers to the question of when and under what circumstances online learning will become the default medium for traditional age students.

According to my college roommates, there are two kinds of beer drinkers: those who want to drink, and those who want to enjoy it. Stories recounted decades later testify to the fact that they were all very much in the former camp. Let’s name our typical drinker of this genus “Bud” after the King of Beers (although actually my roommates were partial to Milwaukee’s Best, affectionately known as “Beast,” because it was even cheaper).

The other camp is found in Brewpubs enjoying artisanal, hand-crafted microbrews with names like Anchor Steam, India Pale Ale, Sierra Nevada and Fat Tire. Let’s call this typical drinker “Sam” after Samuel Adams, the first and largest American microbrew.

Bud and friends constitute 95% of the beer market. Sam is only 5%. But you wouldn’t know it from media coverage of the industry. The vast majority of articles and stories on the industry are fawning profiles of emerging microbrewers.

In the past year, however, even more fawning profiles have been written about Massive Open Online Courses (MOOCs). In the past year, the two Stanford spin-offs, Coursera and Udacity, along with edX, the MIT-Harvard-Berkeley venture, have been featured in virtually every major media outlet. Headlines like “Universities Reshaping Education on the Web” and “The Single Most Important Experiment in Higher Education” convey the breathless tone of the coverage.

While critics point to course completion rates well below 20%, the more fundamental disconnect is that just over a year ago, the day before Stanford professor Sebastian Thrun opened up his fall semester course on artificial intelligence to the world and ended up with 160,000 online students, approximately 3 million other students were pursuing degrees online – attempting to change their lives without ever setting foot on campus. So how is it a “game changer” when a few hundred thousand students enroll in a not-for-credit course online?

The answer is that seems that way only because a lot of Sams become journalists. In the higher education context, read “Sams” as alumni of Samuel Adams alma mater: elite private colleges like Harvard with intensive, immersive residential environments – also about 5% of the market. Buds attend state-supported colleges and universities (but not flagship campuses) or non-elite private schools – the other 95% of the market. For too many Sams, higher education is synonymous with elite colleges and universities. And this distorts much of what passes for opinion and policy making concerning higher education. One result of this myopia may be that that ultimate legacy of MOOCs is somewhat surprising.

***

The media attention on MOOCs has online learning in the spotlight. No longer is it solely the province of for-profits and ambitious regional private universities. So it’s a good time to consider the question some of us have been thinking about for a while, the question that could be called higher education’s singularity: at what point does online learning replace onground as the default medium for traditional- age students in the U.S.? As it turns out, the answer depends on whether you’re a Sam or a Bud.

Like all traditional-age students, Buds pursue higher education to improve themselves, but the improvement is measured by the employment they are able to attain post-degree and the concomitant impact on income and future opportunity. In contrast, Sams and their families have a view of higher education that is more ethereal and close to what America’s leading educational thinker John Dewey believed: that education is not simply a process of gaining knowledge, but of learning how to learn, how to realize one’s full potential, and how to live – not only as an employee, but as a contributing member of society, as a citizen.

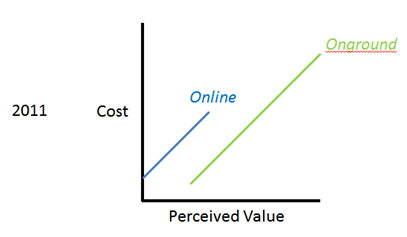

Traditional-age students who approach higher education as Buds will determine whether to enroll in an onground or online program based on a set of options that fall along perceived value curves. Last year, the curves looked like something like this:

At every tuition level, online programs had significantly less perceived value for traditional-age Buds. At the same cost level as the lowest cost onground programs, the perceived value of online programs was probably near zero. And there were no high-cost, high-perceived value online programs for undergraduates.

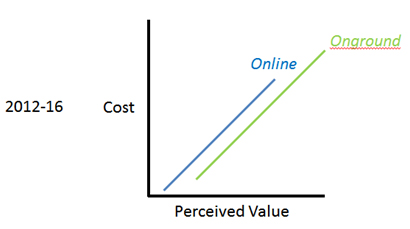

Starting this year, and for the next few years, Buds will see three changes to their online curve:

1) Introduction of lower cost online programs than even the lowest cost onground programs.

2) Introduction of higher cost online programs, with higher perceived value

3) Shift of the curve to the right, as online programs gain greater perceived value at every tuition level.

This shift to the right will be partly due to a range of innovative new technologies we’ve discussed in past letters that will be incorporated into online programs, enhancing engagement, persistence and student outcomes. But much of the shift will be due to MOOCs making online a respectable medium for higher education.

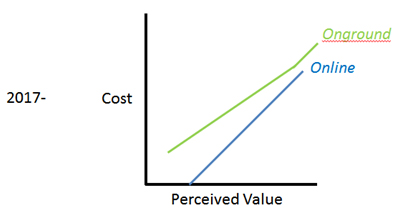

We believe that for Buds, higher education’s singularity happens in the decade after 2017. The online curve will continue to shift to the right for the same reasons including – critically – increasing MOOC activity by elite universities. Meanwhile, the onground curve will be hinging left below the elite level due to continued reductions in governmental support. Also note online programs of real perceived value being offered virtually for free.

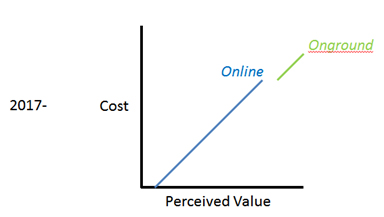

It will be a different story for Sams. This social importance of higher education for Sams will retard the rightward shift of the online perceived value curve for many years, perhaps decades. Equally important, Sams’ overwhelming focus on the value they believe can only be derived from an intensive residential experience leads to myopia, limiting consideration of higher education to the most elite institutions. The result is an onground consideration set that starts at a very high cost and perceived value level: elite colleges and universities.

As a result, Sams and their families, a group that doesn’t like to be behind the curve, may be literally behind the curve in adopting online learning. This could lead to important issues in terms of Sams’ views on, comfort and capability with technology, as well as general social division between Sams and Buds.

One conclusion: it would be a great irony if MOOCs end up mattering a lot more for Buds than for Sams. If so, the MOOCristocracy may be driven to drink – regardless of whether the beer is any good.

University Ventures (UV) is the premier investment firm focused exclusively on the global higher education sector. UV pursues a differentiated strategy of ‘innovation from within’. By partnering with top-tier universities and colleges, and then strategically directing private capital to develop programs of exceptional quality that address major economic and social needs, UV expects to set new standards for student outcomes and advance the development of the next generation of colleges and universities on a global scale.

Comments