Volume VI, #9

Before there was Facebook or Google – even before there was Microsoft – one of the most successful ventures to come out of a college dorm room was National Lampoon. As chronicled in the terrific (but definitely R-rated) documentary “Drunk Stoned Brilliant Dead,” National Lampoon was founded by two editors of the Harvard Lampoon who convinced the inventor of the Diners’ Club credit card to back a national magazine following a series of successful Harvard Lampoon parodies of Mademoiselle (“Exclusive Clothes To Be Caught Dead In”) and Playboy (centerfold with reversed tan lines).

As Founding Editor Henry Beard noted in the film, America “had an attic full of culture that had been accumulating from 1945 to 1970. Nobody had been up there, and we looted it.” National Lampoon took satire to a new level with its infamous Vietnamese Baby Book (“a baby book designed for a Vietnamese baby, so it had things in it like Baby’s First Wound”) and the litigation-inducing parody ad for Volkswagen with a picture of a VW Bug floating in the water (“If Ted Kennedy drove a Volkswagen, he’d be President today.”)

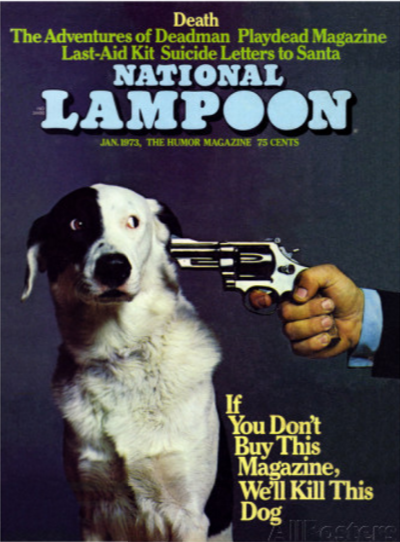

The first cover of National Lampoon featured a half-naked woman next to the banner “Sexy Cover Issue.” (Whenever the magazine wasn’t selling enough, the editors added nudity to the cover.) Of course, the most famous cover of National Lampoon was January 1973. It featured a hand holding a gun to the head of a dog and said: “If You Don’t Buy This Magazine, We’ll Kill This Dog.”

As Michael Gross, the Art Director at the time noted, the Dog issue “was a huge, huge hit, because it’s what every magazine publisher wanted to do. All they wanted to say is ‘buy the [!*%&] magazine’.”

***

While the university from which National Lampoon emerged has never had to resort to such crude commercial means to attract students, lesser institutions have. We’ve become inured to stories about Division I universities recruiting athletes with sex, alcohol and drugs (Colorado, Louisville, Oklahoma State, Oregon, Tennessee). Meanwhile, smaller schools have utilized less Lampoon-ish, but apparently effective means to attract students. Last week, the Wall Street Journal profiled East-West University, a private not-for-profit on the South Side of Chicago that recruits low income students to programs with a 9% graduation rate and where former students make less than high school dropouts. Until last August, the university offered students an iPad if they could convince their friends to enroll. According to a former admissions officer quoted in the article, “Some of these kids couldn’t write at all, you would just look at their essays and you knew they weren’t going to make it.”

Other recent headlines come from misrepresentations that make colleges seem better than they are. Last month a jury determined that Thomas Jefferson School of Law did not defraud a former student by misrepresenting employment statistics despite the fact that many graduates represented as employed worked in jobs outside the field, such as in salons, restaurants, as valets, pool cleaners, or selling books, tractors or lingerie. One juror was quoted as saying “I found it kind of appalling.” In the past few years, more than a dozen similar suits have been brought against law schools.

Misrepresentations extend well beyond law schools. Recent stories of admissions officers intentionally and materially misreporting test scores, GPAs and class rank of enrolled students in order to inflate rankings have tainted schools like George Washington University, Emory, Bucknell, Tulane, Claremont McKenna and Flagler College, where the VP of Enrollment Management memorably explained to The St. Augustine Record: “I really love this college so much, and there had been a decline a little bit in the profile of the incoming class…” And in early April, four graduates of George Washington University’s online master’s program in security and safety leadership sued the university for misrepresenting a series of “scanned-in PDFs of textbooks and Powerpoint slides” as “learning exactly what you learn in a brick-and-mortar classroom” while charging $33k for the privilege – or $4k more than the brick-and-mortar program.

Another questionable tactic utilized by colleges to enroll students is preying on the desire to play a college sport by masking normal tuition discounting as “athletic scholarships,” and stocking teams in popular sports with many more players than needed, or launching new teams in esoteric sports. Then there’s the “bait and switch,” as recently reported by The New York Times: financial aid awarded to freshmen is often reduced in later years. Pine Manor College was specifically called out for significantly reducing aid to sophomores. According to one observer, “it felt like it was a marketing tool. They needed to fill their freshman class.”

These tactics are likely to become more prevalent. As John Katzman recently wrote in Inside Higher Education, the advent of thousands of online programs is creating a marketing arms race for students where “the annual recruiting spend of American Colleges will move inexorably from its current $10 billion to $100 billion a year.”

***

None of these examples come from for-profit universities. Those focused on for-profit abuses aren’t wrong. It’s likely that thousands of students have been conned into enrolling at for-profit institutions via interactions with misleading, overly aggressive and borderline predatory enrollment advisors. For-profit governance increases the risk that the enrollment incentives will be opposed to the interests of students. But as with everything, for-profit governance occurs along a spectrum, with bad actors at one end, good actors at the other. What for-profit critics often fail to acknowledge is that there’s a similar spectrum for traditional universities – one that overlaps with the for-profit spectrum.

Ultimately, it all comes down to decisions made by individual admissions officers. Such decisions are a product of the character of the people hired, their incentives, oversight, and the culture of the institution. At this micro-level, dispositive incentives for making marketing and enrollment decisions may relate to promotions, raises, and increasingly, job security due to increasing fiscal pressure brought on by dwindling enrollment.

The Manichean for-profit/not-for-profit worldview is further complicated by the increasing tendency of traditional institutions to rely on commission-based for-profit agents for the recruitment of international students. As reported in The New York Times, Global Tree Overseas Education Consultants sent “Hurry Up!!!” letters offering “scholarships of up to $17,000” for “spot admissions” to Western Kentucky University to students in India, generating 300 applications “to a college that many had probably never heard of” and where 80% of students admitted through the effort failed to meet English requirements.

America’s colleges and universities must be confident these practices won’t lead to a flurry of complaints and lawsuits from misled students. How else to explain their acquiescence in the current NPRM process to the proposed elimination of arbitration clauses from enrollment agreements? But I think their confidence is misplaced. Individual behavior of admissions officers should be of paramount concern to colleges and universities who have just seen the entire for-profit sector written off due to the magnified actions of a number of bad actors. As overpriced degree programs begin to lose favor in the market, the last thing colleges and universities need is to lose favor as well.

University Ventures (UV) is the premier investment firm focused exclusively on the global higher education sector. UV pursues a differentiated strategy of 'innovation from within'. By partnering with top-tier universities and colleges, and then strategically directing private capital to develop programs of exceptional quality that address major economic and social needs, UV is setting new standards for student outcomes and advancing the development of the next generation of colleges and universities on a global scale.

Comments