Volume V, #20

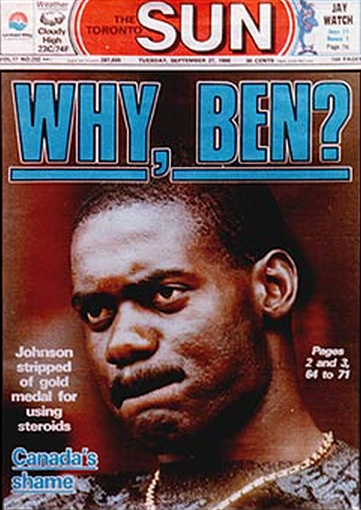

Few things are more upsetting than when a hero turns out to be a villain. Growing up in Canada, we were used to winning all kinds of medals in the Winter Olympics but forever coming up dry in the Summer Games. Canada set a dubious record at the 1976 Montreal Olympics when it became the only host country to fail to win a gold medal. So ahead of the 1988 Games in Seoul, when quiet Ben Johnson emerged as Canada’s answer to America’s brash and flashy sprinter Carl Lewis, all of Canada put Johnson on a pedestal. And when he crossed the line first in Seoul in a record 9.79 seconds – the announcer’s booming “9 7 9” reverberates in my head to this day – the entire country went berserk with joy. Three days later, Canadians received breaking (and heartbreaking) news: our hero had tested positive for steroids and was disqualified. I walked around in a cloud for at least a month. Toronto’s tabloid newspaper, The Sun, summed up the mood with its cover on September 26, 1988.

More than two decades later, Americans had similar empty feelings when Lance Armstrong, cancer survivor and Livestrong Foundation founder, turned out to be a cheat, and when Bill Cosby, model dad, turned out to be a predator. I’m currently struggling with my own disappointment concerning Donald Trump. While far from a hero, I did think Trump was a harmless idiot. Now I see I may have been wrong about the harmless part.

***

America’s colleges and universities are viewed as economic engines of innovation. But while our research universities continue to spin out amazing scientific research and technological advances, annual economic growth has declined from the 3-4% range prior to the recession, to well under 3%. If colleges and universities took some credit for economic growth prior to 2007, could they be responsible for the recent slowdown? Could America’s heroes of economic growth turn out to be villains?

Consider the following:

In summary, there appears to be a strong inverse correlation between student loan debt and the entrepreneurial activities required for economic growth. In 1995, 15% of working adults under 40 were self-employed and 21% student loan debt. In 2010, 12% were self-employed and 37% had student loan debt. Young adults with student loan debt are less likely to apply for business loans (17% of young households with debt vs. 27% of households without debt). And when young adults with loans go into business, they’re not doing as well (an average of 2 employees vs. 9 for those who graduated without debt).

***

In the last UV Letter, I said the following about college affordability: There’s no question that college is expensive. But when nearly half of all students who undertake degree programs fail to complete, and where defaults are concentrated amongst non-completers, it’s hard to argue that affordability should be the end-all and be-all of higher education policy, let alone the basis for a $350 billion commitment. To paraphrase the current Secretary of Education, debt is not catastrophic if students end up with degrees.

As with Ben Johnson, Lance Armstrong, Bill Cosby and Donald Trump, I may have been wrong about this. While college graduate indebtedness may not be catastrophic at the level of the individual, it may be at the level of the economy.

To be fair, I have previously taken on the topic of college affordability and my book, College Disrupted, has a chapter on the Crisis of Affordability. But even if their reason is off-the-mark, the Democratic candidates for president are onto something with their laser-like focus on student loan debt. Could annual economic growth bounce back to the 3-4% range if the entrepreneurial energies of young adults weren’t weighed down by dollars borrowed to pay college and university tuition?

Recently, Lumina Foundation started a conversation on affordability by proposing a benchmark: the “rule of 10.” Net college tuition should be limited to what families can afford to pay by saving 10% of household discretionary income over 10 years plus what students can contribute by working 10 hours per week while attending school.

My best guess is that we don’t get to Lumina’s benchmark through Hillary Clinton’s New College Compact or Bernie Sanders’ free tuition plan, although income-based loan repayment (IBR) is likely to play an important role in lightening the load and releasing entrepreneurial spirits. Just last week a GAO report concluded that the U.S. Department of Education has not done enough to make students aware of IBR options. More than half of all borrowers are eligible for IBR, while fewer than one in seven borrowers take advantage of current IBR programs.

But what really gives me hope that the economic villainy of our colleges and universities is a temporary phenomenon is that both employers and students are starting to indicate a preference for shorter, stackable credentials that convey demonstrable competencies, and that happen to be much less expensive than degree programs. As the popularity of these “just-in-time” programs grows, falling enrollment in expensive degree programs will give colleges and universities no choice but to be heroes, help restore our historic rate of economic growth, and provide some insurance in the unfortunate event our next President is named Trump.

Thanks to Allison Williams for her research assistance with this Letter.

University Ventures (UV) is the premier investment firm focused exclusively on the global higher education sector. UV pursues a differentiated strategy of 'innovation from within'. By partnering with top-tier universities and colleges, and then strategically directing private capital to develop programs of exceptional quality that address major economic and social needs, UV is setting new standards for student outcomes and advancing the development of the next generation of colleges and universities on a global scale.

Comments