Volume III, #22

My experience in intercollegiate athletics started and ended as catcher of the Yale Law School softball team. We’d compete in the University of Virginia Law School softball tournament – the World Series of law school softball. Each participant received a package with welcome statements from the Vice President, the Governor, Senators and Congressmen. It was a convivial affair, at least until we had to play the team from University of Miami Law School. Those guys were all built like Jose Canseco.

I now live in Los Angeles where, contrary to popular belief, there is a professional football team: the USC Trojans. Attending a USC game recently was something of a Mr. Smith Goes to Washington moment for me: a fish-out-of-water, nun-in-a-brothel type of thing.

The numbers surrounding college athletics are as shocking as the scandals erupting weekly from big-time college sports. Division I schools with football spend over $90k per athlete on sports – seven times average spending per student. Universities claim much of this spending is for additional student aid, but the data show it’s only 16%. 84% goes to athletic staff salaries, game expenses and – increasingly – pro-level facilities to attract top recruits. Total Division I sports revenue is $12B. But the crazy thing is that universities lose money on sports and subsidize losses from general funds and additional student fees. For example, University of Cincinnati subsidizes its programs to the tune of $15M each year, on top of a $168.02 student fee per semester specifically for athletics.

Let’s sidestep the issue as to whether student athletes benefit from the current system. Despite a growing chorus of voices claiming unpaid student athletes are exploited, football and basketball players at Division I schools do receive full scholarships. So let’s give the status quo the benefit of the doubt and assume the vast majority do benefit.

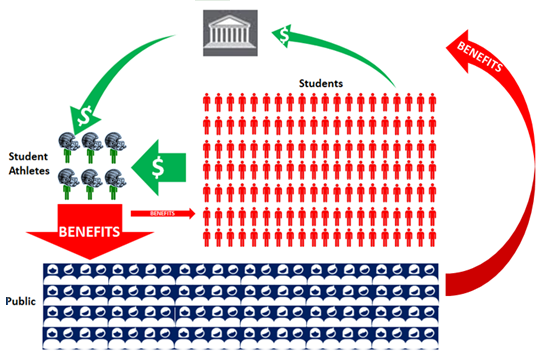

Then the current picture looks like this:

Dollars flow from tuition-paying students to student athletes, while benefits flow to the public or back to the university in terms of prestige and increased enrollment. There are two ways in which tuition-paying students benefit: Increased school spirit and (potentially) enhanced value of their degree through enhanced prestige. (Although, truth be told, Oklahoma State grads aren’t feeling “enhanced” following the five-part Sports Illustrated exposé on the rise of school’s football program.) But tuition-paying students are not capturing their fair share of benefits. Not even close. Which causes me to further question the already questionable adage from Rydell High’s Principal McGee in the movie Grease: “If you can’t be an athlete, be an athletic supporter.”

***

This might be viewed as a curiosity, relegated to a particularly sweaty corner of higher education, if it weren’t instructive for a larger and more important enterprise: research. For years, critics (mainly conservatives) have derided the research output of colleges and universities. Depending on the discipline, anywhere from 45% (sciences) to 98% (arts and humanities) of published research is never cited in any other publication. A 2009 report from the American Enterprise Institute pointed out that over the past five years, the number of published language and literature articles had risen from 13,000 to 72,000.

This outcome is predictable and highly formula-driven. One formula is employed by administrators who determine promotions and salary increases on quantity of publications. (The so-called deans and provosts who “can’t read but can count.”) The second is the damned rankings – all of which include a research component, and many of which are so research-heavy they’re in danger of toppling over. It’s more than simply measuring what’s measurable. It verges on a drunk staggering out of a bar at night, having lost his car keys, and deciding to look under the street light because that’s where he can see. Looking there isn’t particularly helpful. And, by the way, stop looking, because driving in your condition is dangerous!

These formulae ensure that teaching is subordinate to research at nearly all traditional colleges and universities. This is as true in the UK as it is in the U.S. A new report from the UK Minister for Universities estimates that for UK institutions established more than 50 years ago, 60% of total faculty time is allocated to research whilst only 40% is spent teaching students. “The pendulum has swung too far away from teaching,” the report concludes, particularly when UK tuition has now increased to market levels (i.e., £9,000 p.a.). Back in the U.S., a 2005 study in the Journal of Higher Education showed an inverse relationship between amount of time spent in the classroom and a faculty member’s salary. (And now that I’ve cited this study, its author assuredly will enjoy a raise and an even lower teaching load.)

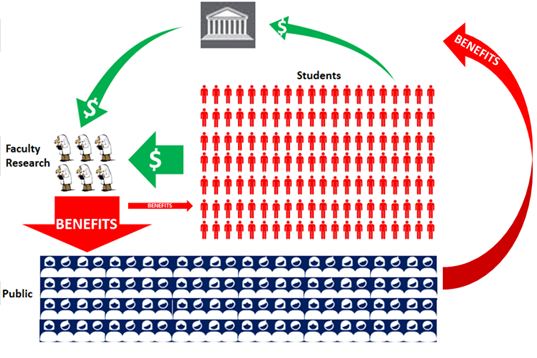

Regardless, you don’t have to be a critic of research to acknowledge that tuition-paying students, whose tuition dollars support a good amount of the research function, are not getting their fair share of the benefits. The comforting narrative of “faculty member at forefront of field imparting the state of the art to students in the classroom” aside (and at the vast majority of institutions, this narrative is science fiction), the picture looks remarkably similar to the athletic one: benefits flow primarily to the public and back to the university rather than to tuition-paying students.

How do colleges and universities countenance this trickery on tuition-paying students? Quite simply: it serves their current missions.

State and not-for-profit colleges and universities tend to have very broad, multifaceted missions. Elements typically include “advancing knowledge” or “serving the public good.” Often there are so many bottom lines there’s effectively no bottom line.

As tuition-paying students focus increasingly on the return to their substantial investment in higher education, and as technology provides students, employers and third parties the means to measure and monitor it, universities will be well-served to focus their missions to serve tuition-paying students over and above any other constituency. It may make them less likely to show up on national television, and it make make 4 a.m. calls from Sweden to faculty members a less common occurrence. But only by doing so will they avoid being disrupted out of existence.

University Ventures (UV) is the premier investment firm focused exclusively on the global higher education sector. UV pursues a differentiated strategy of ‘innovation from within’. By partnering with top-tier universities and colleges, and then strategically directing private capital to develop programs of exceptional quality that address major economic and social needs, UV expects to set new standards for student outcomes and advance the development of the next generation of colleges and universities on a global scale.

Comments