Volume VII, #1

I love community colleges. My mother spent her career as a faculty member at Toronto’s George Brown College where she taught sociology and courses to nursing students on dealing with death and dying, which led to many grim but memorable conversations around the house. But we all recognized that community college paid for our hockey skates and microwave dinners. It also gave me my first job. Before I was old enough to get a job myself, mom nepotistically arranged for a summer position at a George Brown computer camp, helping faculty members and their families learn how to use PCs. I enjoyed it, in particular one faculty daughter. So George Brown College also led to my first date, as I invited her a movie. Sadly, in the first of many youthful decisions that ultimately would be featured on the cover of Bad Judgment Magazine, the film was They Live starring Rowdy Roddy Piper, and – life imitating art – the relationship progressed as well as the film’s plot, which is to say not at all. Suffice it to say, despite my appreciation for the place, the combination of youth and bad judgment meant I didn’t spend much time thinking about the purpose of community colleges.

And so here’s yet one more thing the Obama Administration’s higher education policy has in common with a hormone-ridden 14-year-old Canadian boy. As the first Administration with a faculty member as First or Second Lady (Jill Biden, Professor of English at Northern Virginia Community College) concludes next week, it is the end of an era in which community colleges were viewed as the answer to virtually every ailment plaguing higher education. College affordability? Check: Promote community college enrollments (and make them free). War on for-profits? Check: Attend community colleges instead. But for the unprecedented amount of attention community colleges have received from this Administration, there’s been precious little thinking about their purpose or proper role.

***

Community colleges originated as the first higher education institutions “in the community” when four-year colleges and universities were inaccessible to all but a small segment of the population. They were the first open enrollment institutions and revolutionized accessibility in an era before a college degree became the sine qua non of the labor market. Conveniently, they also delivered the vocational programs “real” colleges didn’t wish to concern themselves with.

So from the outset, community colleges had a split personality: the place to pull yourself up by the bootstraps and transfer, Horatio Alger-like, to a university; and higher education’s grease-stained freaky younger cousin. But crucially, because they were conceived of and led by academics who, by and large, would have preferred to work at a “real” college, they were firmly established on an academic foundation with Presidents or Chancellors, faculty and English Departments, registrars and bursars.

But no matter how much policy makers laud community colleges, the fact remains that these institutions are only fulfilling a fraction of their enormous potential. Completion and transfer rates remain abysmal, almost without exception. And too many vocational programs are being shoehorned into associates degrees, the least valued (and worst value-for-money) credentials in American higher education. It’s why I’m stunned that we’ve been blindly placing our hope, faith and dollars into these institutions for the past eight years, and why I believe that looking to community colleges in their current form to close the skills gap is tantamount to looking to the DMV to invent self-driving cars.

***

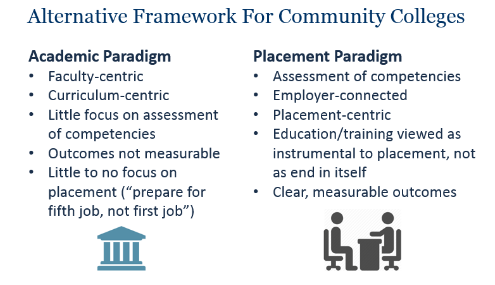

There is another option for community colleges. Instead of constituting them along an academic paradigm, we need to rethink them through a placement paradigm.

A Placement Paradigm for community colleges (let’s call them Placement Colleges) is a hybrid of today’s community colleges and workforce investment boards (WIBs). It starts with the employer and available jobs, but crucially also delivers training and tracks student progress through not only completion, but placement into a good first job.

I’ve written previously about workforce development and WIBs. Positioned as they are as placement organizations, WIBs do a lot to engage employers, keeping track of available positions and what skills employers are looking for. But WIBs are all about speed-to-placement. Very little training gets done, certainly not by the WIBs themselves.

Placement Colleges would keep WIBs’ employer focus, transforming the academic approach to career services (one office among many that students may or may not visit on their way out the door) to an organizing principle. They would also execute on the necessary education and training, but in so doing reduce the importance of “academic” credentials. Pathways to good first jobs in growing sectors of the economy don’t need to be shoehorned into classic credentials. Placement Colleges will be in the business of taking students where they find them, equipping them with new competencies, and delivering them to jobs that (a) utilize their newly acquired skills and (b) provide for upward career and economic mobility. This means no more “one-size-fits-all”; each student is different and requires a tailored pathway.

Without generally understood credentials to fall back on, how will employers make sense of these Placement College graduates? They shouldn’t have to. Because successful Placement Colleges will make employer hiring much simpler and more effective. In the academic paradigm, college graduates receive a credential and a transcript, which employers ignore because they can’t make heads or tails of it. Placement Colleges will provide employers with the elements they need to understand whether a graduate has the competencies to do a job. These elements include: e-portfolios demonstrating relevant student work product; not only industry-specific but employer-specific training, including last-mile training on technical skills, systems or platforms utilized by that employer; and/or try-before-you-buy apprenticeship or staffing models where employers have little to lose in “trying out” candidates (the risk is entirely on the Placement College and the candidate).

Worried that shifting thousands of community colleges to Placement Colleges will bust federal and state budgets? Don’t be. Placement Colleges should require less government funding than the current community college model. First, programs and pathways will be shorter than the current degree- and credit-centric approach. Second, for students who are able to gain the requisite competencies to be placed into higher skill positions in high-demand areas, Placement Colleges will generate revenue from employers in the form of placement fees or tuition reimbursement once employers are convinced to make a permanent hire.

This will allow governments to focus resources on students with the greatest distance to travel, and where the initial placement is likely to be in a low- or mid-skill job, or in a less attractive or slower-growth sector of the economy. By transitioning community colleges to Placement Colleges, we can free up the resources to invest in those students who are falling out of today’s higher education system by the millions, and are being effectively shut out of the modern economy.

***

If you’ve taught sociology at a community college (mom) or English (Dr. Biden), you’re probably wondering how Placement Colleges will continue to provide the first rung on the higher education ladder for those seeking bachelor’s degrees. As Stephen Handel, Associate Vice President for Undergraduate Admissions in the University of California System wrote in last week’s Chronicle of Higher Education, “we encourage our least-prepared students to start college at two-year institutions because they have no admission requirements and are far less expensive than four-year institutions.”

The answer is that they shouldn’t, and they won’t. Encouraging our least advantaged students to start college at a different institution from where they’re expected to complete is educational malpractice, as evidenced by mass casualties from the transfer model (credits lost, students lost). State universities that offer bachelor’s degrees should be required by law to provide comparable open-enrollment, low cost (likely hybrid online) pathways to their bachelor’s degree programs – pathways that are continuous, requiring no “transfer” and involving no risk of lost credits.

Why has the academic paradigm for community colleges persisted for so long? In the same way that our K-12 schools and school districts are often hobbled by decisions made for the benefit of those who’ve opted to enter the education profession, so have community colleges, which have provided good careers to hundreds of thousands of masters- and doctoral-trained educators, like my mom and Dr. Biden. But what about providing careers for workforce, staffing and placement professionals who understand employer needs, hiring processes and how to get students good first jobs? Placement Colleges will provide a bull market for these professionals.

As the Placement College model emerges in the coming years, it will become the new conventional wisdom that community colleges are simply too important to the future of the American economy and the American people to be left to academics.

University Ventures invests in entrepreneurs and institutions that are reimagining the future of higher education and creating new pathways from education to employment. Our portfolio companies are making higher education more affordable, pioneering entirely new approaches to learning, and helping employers think differently about how and where they discover talent. We believe entrepreneurs and institutions that produce meaningful educational outcomes will realize better economic returns. We believe that private enterprises can produce profound social impact, and that public-private partnerships can unlock the potential of mission-driven institutions. Our commitment extends beyond the world of traditional higher education, to the challenge of last-mile training and placement to help individuals showcase their skills and get great jobs in growing sectors of the economy. University Ventures is led by principals with decades of experience as entrepreneurs, investors, and leaders in higher education. Our approach draws upon the values and traditions of higher education to play a sustainable role in transforming the path from education to a stronger economic future for students, universities, and employers.

Comments