Volume VII, #12

I got my first real job at the age of 15, as a busboy at Oliver’s Bakery Restaurant, one of Toronto’s busiest brunch spots. I have so many intense Proustian memories from the strong smells (fresh-baked rolls) and tastes (Café Truffle Torte, still the best dessert I’ve ever had): bringing Sunday’s first customer Lois (always arriving before the wait staff) her coffee and blueberry muffin; polishing wine glasses with steam from a pot of hot water; learning how to punch orders into the computer system (I still recall all the modifiers for eggs – sunny side up, anyone? That’s 118#); and being bullied.

When I started, I was the youngest busboy by two years. A senior busboy – let’s call him “Gord,” and not just because most Canadian males are named Gord – would take coffee from my coffee station, often putting an empty pot back on the burner, leaving burned coffee on the bottom (hell to clean). He’d also put his dishes in my bus pans, requiring me to empty them twice as often and doubling my exposure to that noxious restaurant toxin “bus juice” – the dark gray sickly-sweet smelling liquid at the bottom of each bus pan – my one bad Proustian memory from that job. Finally, he’d collect tips from the waiters and short me every time.

It’s been a while since I’ve been bullied, but last week I had my such first experience on Twitter. In reaction to my last piece on the link between faculty control of curriculum and the challenge of aligning curriculum to employer needs, a number of faculty on “Academic Twitter” took to our President’s favorite medium to denounce the argument and me personally. Ad hominem attacks aside, several academics found “outrageous” the notion that aligning curriculum with employer needs was a goal that faculty members shared. One prominent professor with an army of over 21,000 followers said “Sorry, that isn't a shared goal. It is a questionable goal, in fact.” She then went on to dismiss the notion that students are focused on employment, saying “the research shows today’s students consider community and family [not employment].” Another who was more accepting of the notion that students might care about getting a good first job said “That's a labor-market problem that is not going to be solved by the educational system.”

***

It’s clear that many faculty simply don’t believe New America’s finding that today’s students enroll in postsecondary programs for what appear to be mundane reasons: to improve employment opportunities (91%); to make more money (90%); and to get a good job (89%). So if colleges and universities are going to do a better job addressing this now pre-eminent student need, it’s going to be important for faculty, staff and administrators to understand why employment has become so important to students.

One reason is the exceptionally poor employment outcomes experienced by college graduates during the Great Recession. Most students have older siblings or friends who were underemployed – often significantly – for many years. But if this is the main or only reason, employment concerns should diminish as memories of the Great Recession recede (like the fading Lehman Brothers logo on the coffee mug I keep in my bathroom). But I don’t think they will because there’s a deeper reason for this shift: young people today have much less exposure to paid work.

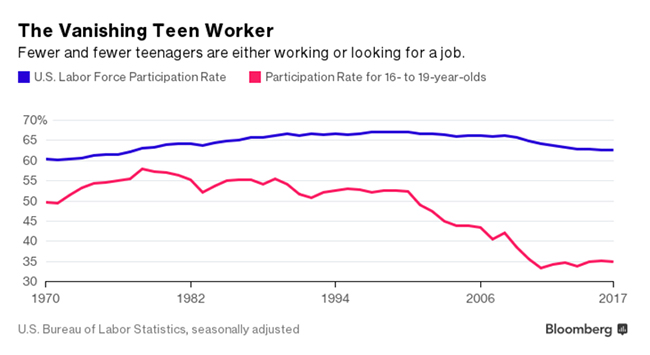

When today’s college and university instructors were in high school, even if they weren’t working as busboys during the school year, it’s likely they worked over the summer. Maybe they scooped ice cream, delivered papers, mowed lawns, or worked as lifeguards. But as Bloomberg reported last week, last summer only 43% of 16-19 year-olds were working or looking for a job – down from nearly 70% a generation ago. The Bureau of Labor Statistics predicts teen workforce participation will drop below 27% by 2024.

Why is this occurring? Bloomberg cites crowding out by older workers and immigrants. Other possible reasons are stricter teen driving laws and compressed summer calendars. But the most plausible explanation is that jobs like busboy have been devalued by society in general – and parents in particular – as useful steps on the road to a successful career. Instead, students are being encouraged to study and participate in as many extracurricular activities as possible in order to burnish their college applications. Jeff Selingo noted as much in his Washington Post column last week, quoting one expert as saying: “Upper-middle class families and above have made the determination that college admissions officers devalue paid work and that if you’re not pursuing a hectic schedule of activities you’ll be less appealing to colleges.”

I agree with Jeff that sacrificing paid work at the altar of college admissions and the almighty bachelor’s degree has not only been short-sighted, but harmful. As Jeff noted, his job in a hospital kitchen “was probably the worst job I ever held, but it was the first time I wasn’t surrounded by my peers, so it taught me how to interact with people of all backgrounds and ages. I also learned the importance of showing up on time, keeping to a schedule, completing tasks, and paying attention to details (after all, I didn’t want to mess up a tray for a patient on a specific diet).” So whereas college and university faculty members developed their soft skills in hospital kitchens – and while I learned to navigate jerks like Gord – their students are at a material disadvantage in this regard (providing some basis for employers’ increasing complaints about the soft skills of Millennials).

This disconnection from paid work has been exacerbated by the rise of unpaid internships during and after college. The National Association of Colleges and Employers (NACE) reports the percentage of college graduates participating in at least one internship is now over 80% (up from less than 10% a generation ago). Unpaid internships are technically illegal unless the employer is a not-for-profit organization, or unless interns receive college credits. Sadly, by broadly awarding credits for unpaid internships, many colleges and universities are enabling this system of internship-peonage, thereby furthering young people’s distance from paid work.

The result is that for most Millennials – and now Gen Z – there’s no sense of easing in to paid work, no gradual evolution. It’s now binary: at the end of college, switch off childhood and switch on employment and adulthood. The anticipation of this sudden shift is producing a great deal of anxiety around the issue of employment, and the first paid job in particular. (An anxiety that today’s faculty, Jeff and I never felt because we all had a sense we were employable – maybe not in the jobs we wanted, but we had a clear sense we would be able to get by.) Of course, the crisis of college affordability and the concomitant mountain of student loan debt makes this anxiety even more acute.

***

I recall a similar sense of anxiety from my job at Oliver’s. When I was promoted to waiter at the age of 17, I was often tasked with Section 6 – the restaurant’s largest section, closest to the front with appealing window-side tables. It was all too easy for hosts and hostesses to accede to customer requests and seat all the tables at the same time. When it inevitably happened – switch from deserted section to a dozen tables demanding coffees and delicious desserts like the insanely amazing Café Truffle Torte – I’d find myself “in the weeds,” literally in a dreamlike state, unable to process what to do next. Whenever I got Section 6, I spent the whole shift dreading this moment. As I think about it now, while being “in the weeds” was taxing, the extreme negative feelings I still have for Section 6 can only be explained by the fact that the anxiety was worse.

So when it comes to employability and aligning curriculum to meet employer needs so students are more likely to get a first job, academics could be more understanding. Many of their students are dreading graduation, paralyzingly anxious at the thought of being “in the weeds” in terms of paid work.

Perhaps the real reason I was bullied last week is that this topic gives many professors anxiety about their own employment. But as we’ve learned, it doesn’t have to be a binary shift. By talking it through and getting the faculty comfortable with the inevitable evolution of our system of higher education to one that is more aligned to employer needs, I’m hoping to alleviate some of this anxiety.

Comments