Volume III, #10

My first lesson about the importance of simplicity in higher education occurred in the early 1990s when Yale made a major investment in its telecommunications infrastructure. The grey-box security phones placed around campus at gates and outside residential colleges and classroom buildings were upgraded. The new phones were superior in several respects. First, they were Yale blue. Second, they featured a big red alarm button. Third, instead of a receiver, they had a speaker that operated at high volume. The complete package looked like a police car and screamed security.

My roommates and I had great affection for the grey-box phone outside our dormitory. Someone had written the phone’s 5-digit number inside the box and we spent countless hours calling the phone to see if a passerby might pick-up. If so, antics ensued. We’d pretend to be campus security and ask what was in their backpack. We’d be trying to deliver a pizza, or casually offer some Grey Poupon. We would compete to keep ambulating interlocutors on the phone as long as possible.

One day our grey-box was replaced with a gleaming new blue phone. We dialed the 5-digit number. Lo-and-behold, the phone picked up automatically, providing a booming megaphone for a group of sophomores on the cusp of redefining sophomoric.

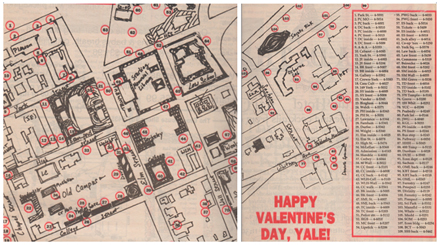

One of the most important lessons I learned in college is that building a simple product is really hard work. But if you want your product to be adopted and used, you’d best do the work. And so we did. We found one of the few phones on campus with caller ID and divided Yale into quadrants – each of us charged with running or biking from blue phone to blue phone and calling into the central number with our coordinates. Our friend at central wrote down each number and location. By the end of the night, everyone was exhausted.

The resulting product was a Blue Phone Map we published for the entire campus as a Valentine’s Day present.

Ostensibly for security purposes (i.e., follow your friend as she walks back to her room), the map was immediately abused as students explored the many different ways of playing the “Hey, I’m stuck in this blue box” joke. The product was simple and used extensively. It also got us called into the Dean’s office.

***

It is far more difficult to be simple than to be complicated; far more difficult to sacrifice skill and easy execution in the proper place, than to expand both indiscriminately. - John Ruskin, Victorian Artist turned Art critic

Complexity kills. Complexity sucks the life out of users, developers and IT. Complexity makes products difficult to plan, build, test and use. Complexity introduces security challenges. Complexity causes administrator frustration. - Ray Ozzie, Microsoft Chief Architect turned Microsoft critic.

Fast forward 20 years: Caller ID phones are the norm and our increased reliance on technology has clarified the singular importance of simplicity in product design. Years before he conceived the iPod, iPhone and iPad, Steve Jobs was designing videogames for Atari. Jobs hated complicated manuals, saying products needed to be so simple that a stoned freshman could figure them out. The only instructions for the Star Trek game he built for Atari were: “1. Insert quarter. 2. Avoid Klingons.” His main demand of iPod, iPhone and iPad product designers was: “Simplify!” If he couldn’t figure out how to navigate to something or if it took more than three clicks, he would flip out.

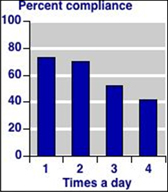

Simplicity isn’t only important for the design of gadgets and games, it also directly translates to adoption and effective use of services. In medicine, compliance with a prescribed treatment regimen is directly correlated to the simplicity of that regimen. Studies have demonstrated that compliance with a single prescription medication is inversely correlated with the number per day. Compliance is nearly half when daily intake goes from 1 to 4x.

If any product or service should be designed so that a stoned freshman can figure it out, it should be higher education. Sadly, higher education may be the least simple, most complex product or service purportedly designed for mass consumption.

According to research presented in April at the annual meeting of the American Educational Research Assocation: Trying to earn a degree at a community college? You might as well be going to school at the DMV. Focus groups conducted at Macomb Community College, a two-campus system in Michigan offering over 100 degree programs to 48,000 students revealed that very few students are able to navigate the complexities of enrollment, financial aid, transcript requests, prior credit recognition, program selection, course selection and scheduling. Faced with so many choices, students either avoid making decisions or make decisions they later regret. For example, “students might select whichever courses are most convenient for their schedule, and then later find out they’ve wasted their time and money on a course that doesn’t count toward their degree… For some of them, this could be the last straw which breaks their tenuous attachment to college.” This is particularly so when students are enrolled at multiple institutions simultaneously in an attempt to get the requisite courses – something increasingly common as a result of our approach to funding (i.e., rationing) at state-supported institutions – and when 52% of students entering community colleges are relegated to remedial courses.

Whereas the iPod, iPhone and iPad had a single architect (or maybe two) who valued simplicity above all and would stop at nothing to achieve it, the product design of colleges and universities is by (faculty) committee. And the committee typically has difficulty agreeing on anything, let alone the importance of simplicity. Moreover, as nearly half of U.S. students enrolled in undergraduate higher education programs are at community colleges and 75% of total enrollment in higher education is concentrated at state-supported institutions, having just filed our taxes, it’s seasonally appropriate to acknowledge that government and government supported institutions are not good at simplicity.

Complex rules are not only hard to follow, complexity provides our cunning brains with a wide expanse of excuses for not following rules. It’s no wonder Steve Jobs didn’t last four years and 50% of students who start college in this country never finish. So it’s infuriating to read articles about a supposed new trend towards DIY (do-it-yourself) degrees. Written by journalists from the “one anecdote = a trend” school, these articles profile a student or two and then feature a quote like this one from Molly Corbett-Broad, President of the American Council on Education: “We are at or approaching a point of significant transformation where you will be able to snap modules together from a wide array of choices.” Coverage like this lulls us into a slumber when we should be as accepting of the complex status quo as the javelin thrower in Apple’s famous 1984/big brother advertisement.

***

The fix here isn’t getting faculty, administrators or government to prioritize simplicity. That would be a singularly unrewarding exercise. Rather, it relates to an insight that Sebastian Thrun had when he announced Udacity (but one that relates to online delivery in general, not the peculiar MOOC genre):

“We really set up our students for failure. We don’t help students to become smart. I started realizing that grades are the failure of the education system. [When students don’t earn good grades, it means] educators have failed to bring students to A+ levels. So rather than grading students, my task was to make students successful. So it couldn’t be about harsh, difficult questions. We changed the course so the questions were still hard, but students could attempt them multiple times. And when they finally got them right, they would get their A+. And it was much better. That really made me think about the education system as a whole. Salman Khan has this wonderful story. When you learn to ride a bicycle, and you fail to learn to ride a bicycle, you don’t stop learning to ride the bicycle, give the person a D, and then move on to a unicycle. You keep training them as long as it takes. And then they can ride a bicycle. Today, when someone fails, we don’t take time to make them a strong student. We give them a C or a D, move them to the next class. Then they’re branded a loser, and they’re set up for failure. This medium has the potential to change all that.”

Thrun is talking about competency-based learning. Competency-based learning (not MOOCs) is the game-changer that online delivery makes possible. It will take a ton of work over the next 20 years to move our higher education system from a clock-based to a competency-based model. But when we do, higher education will be much simpler to navigate and use. Transfer credits and courses that don’t apply to your degree will be as anachronistic as grey-box security phones. Self-paced programs will radically lower costs and limit the role and need for financial aid (itself a major source of complexity). Student competencies will be laid bare before prospective employers and matched to job descriptions. Adoption rates will soar; drops will plummet.

If the competency-based Western Governors University was the higher education equivalent of the iMac, then this year, the first iColleges, are coming online. Patten University and Southern New Hampshire have announced their plans. In a few years, high school graduates in North Carolina will earn diplomas showing readiness for university, community college, or careers. The pitter patter of other universities launching new competency-based programs will soon take on a distinctly disruptive tone.

Steve Jobs liked to say simple was a lot harder than complex: “You have to work hard to get your thinking clean to make it simple. But it's worth it in the end because once you get there, you can move mountains.” These new institutions will take time and a lot of hard work to build. But the iColleges will fundamentally transform the seemingly immovable mountain of higher education.

University Ventures (UV) is the premier investment firm focused exclusively on the global higher education sector. UV pursues a differentiated strategy of ‘innovation from within’. By partnering with top-tier universities and colleges, and then strategically directing private capital to develop programs of exceptional quality that address major economic and social needs, UV expects to set new standards for student outcomes and advance the development of the next generation of colleges and universities on a global scale.

Comments